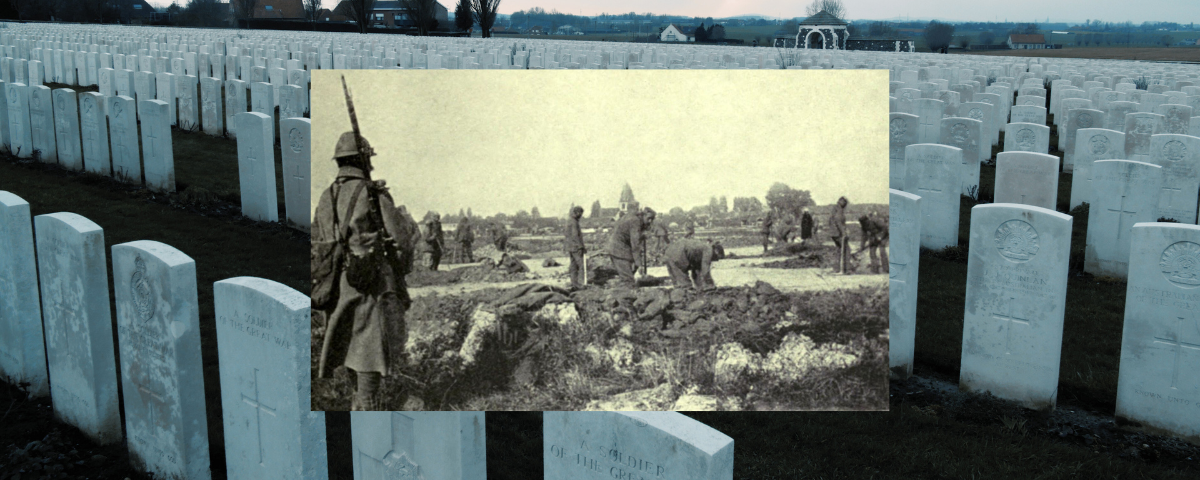

The “ANZAC Spirit” is legendary within Australian identity, but historian Daniel Reynaud thinks it fails to capture the full breadth of those who’ve served our country, namely William “Fighting Mac” Mackenzie who sits on the edge of the stereotype.

Key points:

- In World War I Mackenzie earned a reputation for his unwavering work ethic and lifting the spirits of the soldiers in harsh times.

- Nowadays Mackenzie’s life is all but forgotten, which Daniel thinks reflects the limits of the “ANZAC” stereotype.

- “What we don’t recognise is [that]… most of those men had a Christian background, and many of them were quite active believers.”

- Listen to this conversation in the player above.

Mackenzie was a chaplain who became one of the most famous Anzacs.

In World War I Mackenzie volunteered alongside men in Egypt, Gallipoli and France earning a reputation for his unwavering work ethic and lifting the spirits of the soldiers in harsh times.

“He was legendary for his spontaneous concerts,” Prof. Daniel told Hope 103.2.

“He’d walk along the billets and say, ‘Come on men, we’re going to have a concert, what can you do?’.

“In no time at all he’d have this roaring, boisterous, lively concert going.”

In World War I Mackenzie earned a reputation for his unwavering work ethic and lifting the spirits of the soldiers in harsh times.

In Daniel’s book The Man the ANZAC’s Revered we learn that when Mackenzie returned to Australia in 1918, his popularity rivaled that of the Prime Minister.

A crowd of 7000 welcomed him home and regarded him as “a celebrity”, with former servicemen and their families gravitating toward him for decades to come.

Nowadays Mackenzie’s life is all but forgotten, which Daniel thinks reflects the limits of the “ANZAC” stereotype.

“We’ve made quite an important thing of remembering the ANZAC’s,” Daniel said.

“And we’ve given them a particular character – they’re the bush larrikins.

Nowadays Mackenzie’s life is all but forgotten, which Daniel thinks reflects the limits of the “ANZAC” stereotype.

“But what we don’t recognise is the quite great extent to which most of those men had a Christian background, and many of them were quite active believers.”

The dilemma for Mackenzie is he embodied what the “typical Aussie digger” loved to hate.

“How do you fit an evangelistic man who preaches against the booze and the betting and the language and the brothels [into] the stereotype of the typical ANZAC?,” Daniel said.

However, if we forget the stories of people like Mackenzie, we also forget to honour the personal cost of their service, and the trauma exposure to war left with them.

“Chaplains tended to suffer from that at a higher rate,” Daniel said.

“What we don’t recognise is [that]… most of those men had a Christian background, and many of them were quite active believers.”

“Because they had to deal with every death.

“Soldiers only had to deal with the death of their mates, or the death of people around them.”

“After The Battle of Lone Pine in Gallipoli Mackenzie buried 450 soldiers in three weeks, and by the end of it he’d lost a third of his body weight.”

In writing The Man the ANZAC’s Revered, Daniel wanted to present “an honest and full biography that just let [Mackenzie’s] actions speak”.

“I think it’s time we broadened our understanding of the ANZAC’s to include such men as Mackenzie,” Daniel said.

“Who was an inspiration for so many soldiers.”

Listen to this conversation in the player above.

Feature image: Photos by CanvaPro

Get daily encouragement delivered straight to your inbox

Writers from our Real Hope community offer valuable wisdom and insights based on their own experiences!